Decision making is the process we use to identify and choose alternatives, producing a final choice, which may or may not result in an action. It's basically a [[problem solving]] activity, and it can be more or less [[Thinking|rational or irrational]] based on the decision maker's [[values]], beliefs, and (perceived) knowledge.

- Living a good life depends on our ability to make good decisions constantly.

- Not perceiving the world accurately makes us worse at making decisions.

- The decisions you make fall into two categories:

- [[Focus|Prioritizing]] — Which path should you take first?

- Allocating — How much [[Focus|Attention]], [[Time]], and capital should you spend on this?

- Separate decisions into four possibilities based on the type of decision:

- Irreversible and inconsequential.

- Irreversible and consequential. These are the ones that you really need to focus on. Irreversible decisions tend to have a long lag time from decision to feedback, and are often more consequential. They must be dealt by becoming more creative, having more slack, being more equanimous, and pruning more efficiently.

- Reversible and inconsequential

- Reversible and consequential. Perfect decisions to run experiments and gather information. Reversible actions can be stopped if they turn out to be bad, and tend to work well with tight [[Feedback Loops]].

- Set a default decision and work from there.

- Realize that the possibility space is much bigger than you initially think. Take some distance and see the decision through different lenses. The bottleneck to doing something is often knowing that it's even an option.

- How un-doable is a decision? If an idea is fully un-doable, make it as quickly as you can. When a decision is something that you can't take back, then it's worth really, really understanding. Aim for preserving optionality.

- To maximize your long-term happiness, prioritize the projects you'd most regret not having pursued by the time you're old and looking back at your life.

- Gather all the information you can. Then, schedule [[time]] to think deeply about it. Brain-dump your thoughts on the problem - what's going wrong, why is it inefficient? Try to understand it in as much detail as possible.

- Learn from the mistakes of others. You can't live long enough to make them all yourself.

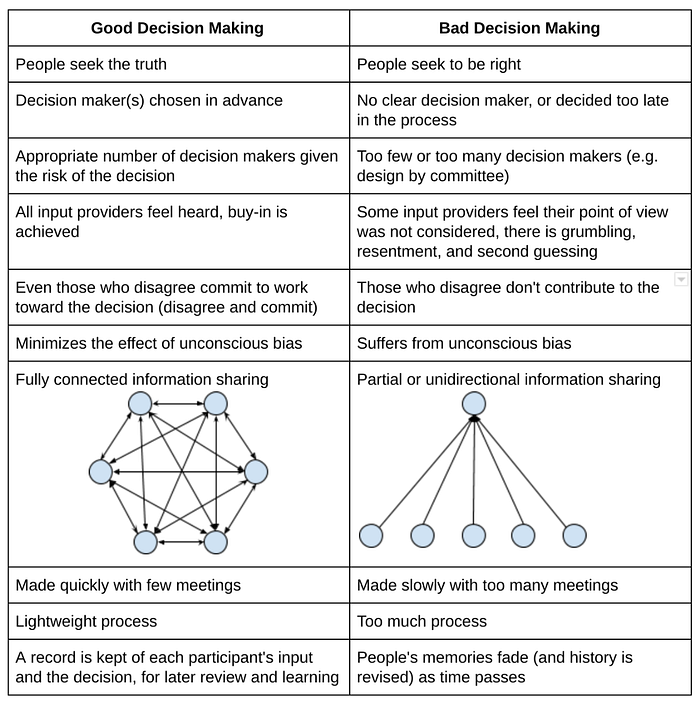

- Remember that too much information increases confidence not accuracy. Share all the information with other stakeholders. [[Openness|Transparency]] is key for group decisions.

- Most decisions should probably be made with somewhere around 70% of the information you wish you had. If you wait for 90%, in most cases, you're probably being slow.

- The fog of the future hides vital information.

- If all options are similar take the harder one in the short term (Hard decisions easy life, easy decisions, hard life).

- If the cost of a wrong decision is tolerable, choose a single decision maker to capture the speed bonus. If a wrong decision would be irreversible or too costly, add more decision makers.

- Look for win-win decisions. If someone has to lose, you're not thinking hard enough or you need to make structural/[[Incentives]]/environmental changes. Avoid false dichotomies. When given two great options, choose both. When given two horrible options, choose neither. Think outside the box!

- The rule of 5. Think about what the decision looks like 5 days, 5 weeks, 5 months, 5 years, 5 decades.

- Flip your goal state with your current state, and ask if you would like to go back there. This helps you switch around any biases that might be influencing your decision-making.

- Ask what information would cause you to change your mind. If you don't have that information, find it. If you do, track is religiously. Collect [[Feedback]] and be open to change outcomes.

- We are all susceptible to bias, almost all the time. A way to detect bias and minimize the decision impact is to run it by a bias checklist.

- Noticing biases in others is easy, noticing biases in yourself is hard.

- There are many reasons why smart people may make a poor decision; Overconfidence, Analysis paralysis, Information overload, Lack of emotional or physical resources, ...

- Decision making styles:

- Intuitive vs. Rational. System 1 vs System 2.

- Maximizing vs. Satisficing. Go for the optimal decision or simply try to find a solution that is good enough.

- Well defined goal vs. blurred objective. [[Planning]] all the details or trying to be as flexible as possible.

- Anecdotes are not data. Good data is carefully measured and collected information based on a range of subject-dependent factors, including, but not limited to, controlled variables, meta-analysis, and randomization.

- Most experts aren't communicators and most communicators aren't experts. This often results in research on issues being spun with a narrative by the time it reaches the public.

- Beware of cases where the decision lies in the hands of people who would gain little personally, or lose out personally, if they did what was necessary to help someone else. They have no skin in the game and no incentives.

- You have a plan. A time-traveler from the future appears and tells you your plan failed. Which part of your plan do you think is the one that fails? Fix that part.

- When consensus doesn't occur it's because there isn't a clear answer or because there is a conflict between groups. In these situations it's up to management to make a decision so the organization can move forward.

- If you're in between two decisions, don't half-ass both of them! Do one 100%, then do the other 100%.

- People reason more wisely about other people's problems than about their own.

- When you share something, add the level of confidence you have on it.

- Understand your personal stance on the trade-off of compromise versus purity. Given a choice between two alternatives, often both expressed as deep principled philosophies, do you naturally gravitate toward the idea that one of the two paths should be correct and we should stick to it, or do you prefer to find a way in the middle between the two extremes?

- It's often not how much force you can bring to bear, so much as whether you can apply that force effectively.

A decision making framework is only needed when there is lack of clarity about a decision that is higher risk. Higher risk can mean that the decision has long term implications or that it can be costly to unwind if the wrong decision is made.

This is how to make decisions.

- Set the parameters. Decision date, revision date, owner, type (binary, prioritization, choice, ...)

- Define the problem. Understand the problem at hand. Look for examples, think about, come up with explanations, get data, ...

- Establish the criteria. List all the factors you want to consider before making a decision.

- Present data and consider the alternatives. Do enough research to have a few solid alternatives. Once you understand what's going wrong, think about what behavior/environment changes could be that would lead to better outcomes

- Identify the best alternative. See which alternative makes most sense based on your criteria.

- Develop and implement a plan of action. Act on that decision. Figure out which action changes, and what concrete things should trigger them - make it something that will actually work in the moment, and can be implemented

- Evaluate the solution. In order to make better decisions over time, examine the outcomes and the feedback you get. The evaluation should be made without taking account the outcome since it wasn't known at decision time.