SigNN is the first app which can translate ASL (American Sign Language) in real-time. It is free and available for download on the Play Store. Most of our raw data is also publically available on Kaggle.

When using SigNN, please sign with your left hand. Right-hand support is not implemented. Additionally, please make sure your hand is not at an extreme angle when signing the ASL alphabet.

This tool can help people learn sign language by validating if they are clearly signing their word. If SigNN can understand your ASL sign, then an ASL signer certainly could as well.

This tool may also get people interested in ASL and the facilitation of communication with those who have difficulty communicating through speech. There right now exists expensive sign language translation gloves, but we hope to see more affordable and scalable solutions in the future.

SigNN stands for Sign Neural Network and is a proof of concept built upon MediaPipe, a Machine-Learning Pipeline made by Google. It shows that real-time sign language translation is now possible on mobile devices. SigNN was developed by a group of students at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

A company or group with more resources can create a more accurate neural network and provide support for not only the ASL alphabet, but the more common words. While we may be the first on the app store, we hope that many improved versions will follow.

- Arian Alavi

- Vahe Barseghyan

- Rafael Trinidad

- Gokul Deep

- Kenny Yip

- John Kirchner

- Daniel Lohn

- Conor O'Brien

SigNN is only supported on Ubuntu 18 and Android. If you have an Android phone, it is possible to run SigNN on Ubuntu and use the Android as a webcam.

In order to compile, first download the pre-requisites for MediaPipe so that you may compile the normal "handtracking" example that they have for your target OS. For mobile and Ubuntu (GPU) it is required to install GPU support as well, so a virtual machine will not work.

To compile our project, run:

bazel build -c opt --copt -DMESA_EGL_NO_X11_HEADERS --copt -DEGL_NO_X11 mediapipe/examples/desktop/hand_tracking:hand_tracking_gpu

If you own a webcam, run:

sudo GLOG_logtostderr=1 bazel-bin/mediapipe/examples/desktop/hand_tracking/hand_tracking_gpu --calculator_graph_config_file=mediapipe/graphs/hand_tracking/hand_tracking_desktop_signn.pbtxt

To compile our project, run:

bazel build -c opt --define mediapipe_DISABLE_GPU=1 mediapipe/examples/desktop/hand_tracking:hand_tracking_cpu

If you own a webcam, run:

sudo GLOG_logtostderr=1 bazel-bin/mediapipe/examples/desktop/hand_tracking/hand_tracking_cpu --calculator_graph_config_file=mediapipe/graphs/hand_tracking/hand_tracking_desktop_signn.pbtxt

If you do not own a webcam: Download droidcam on the play store for Android and (follow their steps to setup Droidcam on Linux)[https://www.dev47apps.com/droidcam/linux/].

Prefix your run command with sudo LD_PRELOAD=/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libv4l/v4l2convert.so to make use of Droidcam.

Example for GPU:

sudo LD_PRELOAD=/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libv4l/v4l2convert.so GLOG_logtostderr=1 bazel-bin/mediapipe/examples/desktop/hand_tracking/hand_tracking_gpu --calculator_graph_config_file=mediapipe/graphs/hand_tracking/hand_tracking_desktop_signn.pbtxt

It is recomended to use NDK Version 21. To compile our project, run:

bazel build -c opt --config=android_arm64 mediapipe/examples/android/src/java/com/google/mediapipe/apps/signnonehand:signnonehand

Transfer to Android phone through ADB by running:

adb install bazel-bin/mediapipe/examples/android/src/java/com/google/mediapipe/apps/signnonehand/signnonehand.apk

The following is our research paper in markdown format. It can also be accessed by PDF here: https://github.com/AriAlavi/SigNN/blob/master/One-Handed%20American%20Sign%20Language%20Translation%2C%20With%20Consideration%20For%20Movement%20Over%20Time%20-%20Our%20Process%2C%20Successes%2C%20and%20Pitfalls%20(2020).pdf

One-Handed American Sign Language Translation, With Consideration For Movement Over Time - Our Process, Successes, and Pitfalls (2020)

The goal of SigNN is to develop a software which is capable of real-time translation of American Sign Language (ASL) into text. Due to resource constraints, the scope has been limited to completing reliable translation for the ASL alphabet. We have achived this objective using MediaPipe: an alpha-stage framework for building multimodal, cross platform, applied ML pipelines. Almost all data used to train our neural network was self-collected, aggregated, and analyzed through the use of scripts written in Google Colab.

Developing a tool for sign language has been a popular project for the past two decades. A primitive start to the project of sign language translation was the sign language glove. In 2002, a MIT student was among the first to achieve a basic form of translation through the use of a glove. Since then, many different types of sign language glove prototypes have been made. Yet, gloves have had many limitations. One obvious limitation is the impracticality of carrying around a glove at all times. The high cost for the gloves is another limitation. Finally, sign language translation requires not only the use of hand tracking, but facial tracking as well. There is also an ethical problem with gloves. It's dehumanizing to those who rely on ASL as their primary form of communication, asking them to put on a glove in order to be understood.

As AI and computation power has improved, people attempted to develop a tool for sign language translation through the use of computer vision. These attempts have been done through the direct interpretation of pixels for sign lagnuage translation - it has been found to be very ineffective. Another popular path to vision-based sign language translastion has been to build the translator on top of a framework which already provides the coordinates of the hands. This simplifies the problem greatly from "Given an image ,what am I signing?" to "Given a series of hand coordinates, what am I signing"

There have been a few different frameworks created which can detect the position of hands. The most famous of them is of course, OpenPose. OpenPose not only interprets the hands of the image, but also the arms and face, which are other vital parts of sign language translation.

From OpenPose

As impressive as OpenPose is, it faces one major challenge: speed. It is extremely slow and cannot be run on the average smartphone or computer in the foreseeable future. As impressive as OpenPose is, it faces one major challenge: speed. It is extremely slow and cannot be run on the average smartphone or computer in the forseeable future. By the developers' own measurements, the model runs at .1 FPS to .3 FPS average depending on the OpenPose model used. . Such speed is nowhere near sufficient to enable real-time sign language translation. Perhaps if it is run in a powerful, remote server it could work. Then, it would require users to be prepared to pay an expensive monthly subscription. Without the issue of speed, Openpose genrally was found to be an effective framework for sign language translation and the choice of many machine learning researhers.

In June 2019, the developers at Google released MediaPipe into the open-source enviornment on GitHub. Unlike Openpose, MediaPipe is not just a neural network but is an entire framework for the management and execution of neural networks on streams of data (such as video and audio). MediaPipe is still in the alpha stages and lacks much comprehensive documentation. Compared to OpenPose, it should be less effective for general sign language translation, given that the model only detects hands and not the entire arm plus face. (As of October 2020, we have found that MediaPipe has added OpenPose-like tracking and detailed facial feature tracking). Yet, what makes MediaPipe more impressive the OpenPose in practice is its impressive framerate and ability to run on any environment. More information is available in this review of MediaPipe.

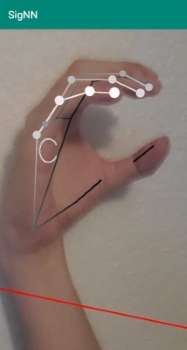

From MediaPipe

Sign language translation has yet to be done comprehensively with MediaPipe, given that it is a brand new and yet-to-be documented technology. Our motivation for this project is to be among the first to use this promising new technology and apply it to a problem that many have attempted to tackle in the past.

When it comes to complete sign language translation, there are three main phases:

-

Recognition of hands in motion, with some idea of hand persistence (left hand versus right hand)

-

The translation of individual words

-

The interpretation of words into sentences (ASL does not use the structured grammatical rules of English)

Phase 1 is partially done by the hand tracking neural network provided by MediaPipe. MediaPipe can only detect the presence and position of hands , but cannot differentiate between the left hand and right hand (not true as of October 2020). Our team has had many discussions on how to tackle this issue, here are some solutions we proposed:

-

Detecting the subtle difference in left and right hand finger lengths

-

Using the difference in skin color on the front and back of the hand

-

Asking the user to calibrate by having their hands to their sides and then associating that position with left and right. Then updating left and right each frame to whichever hand is closest to the last known position of left and right

In the end, the lack of hand persistence did not pose a substantial problem due to the limited scope of the sign language translation we aimed to complete. If we wished to extend our scope to words, it would be necessary to track the handedness of each hand as well.

Phase 2 is in the realm of SigNN. We are to, given the coordinates from phase 1, output which character the user has signed. To completely finish phase 2, the neural network must be able to identify most words in ASL. This task would have been far too ambitious for our team, as we do not have the resources to collect all that data necessary.

We began our project by trying to break into the black box that was MediaPipe. While there is some basic documentation, much of what we learned was through experimentation and modification of the source code. After a month, we finally had a good idea of how to modify MediaPipe for our purposes.

The diagram above shows the MediaPipe graph for detecting and rendering the position of a hand in a video. MediaPipe works through a system of graphs, subgraphs, calculators, and packets.

-

Packets: Packets is simply any data structure with a time stamp. In the shown diagram, input_video is the packet that is fed into the graph. The HandLandmark subgraph takes in the packets: NORM_RECT and IMAGE while outputs the packets: NORM_RECT, PRESENCE, and LANDMARKS. Packets are sent between calculators on each frame.

-

Graph: A graph is the structure of the entire program. The entire diagram itself is a graph called "Hand Tracking CPU". Graphs are defined in special .pbtxt files and are read at the start of run-time, meaning that they can be modified without recompiling the code

-

Calculators: Calculators can have inputs and outputs. They run code on creation, per frame, and on close. An example of a calculator could be one that takes in coordinates of hands and outputs those coordinates being normalized. Another example of a calculator could be one that takes in a tensorflow session and a series of tensors and outputs detections. Some examples of calculators in the diagram are: FlowLimiter, PreviousLoopback, and Gate

-

Subgraph: A subgraph is a series of calculators grouped into a graph. Subgraphs have defined inputs and outputs and help to abstract what would be an otherwise over-complicated .pbtxt file and diagram. The subgraphs in the diagram are in blue and are: HandLandmark, HandDetection, and Renderer

Read more about MediaPipe's structure here

We were then able to modify the structure of MediaPipe's hand tracking graph to output the coordinates of the hands, which were hiding in HandLandmark as the packet called LANDMARKS.

The example shown above is the modification we made to the Multiple Hand Detection CPU graph in order to get output to the console. From there, the output could be piped into a python application for data collection.

This is an example of the output we modified MediaPipe to output. On the left is the rendered image that MediaPipe normally outputs and on the right is a graph of the series of coordinates that we modified MediaPipe to output.

We also looked at OpenPose as an alternative to MediaPipe. We figured that tracking the arms and the face would significantly increase our accuracy levels. However, most of our collected data did not include the entire upper body. As a result, only ~1,000 / ~6,000 images could be used to train the neural network. After training the neural network we received an unsatisfactory ~77% accuracy. Lastly, OpenPose was prohibitively slow on our laptops and we found that it could not be used to translate sign language in real-time. As a result, we decided to stay with our original framework of MediaPipe.

Data collection was a crucial part of increasing our accuracy. We would have preferred to use publicly available data to train our neural network. However, there were very few sign language data sets and the ones that did exist were of very low quality. As a result, we decided to create our own dataset. While the idea seems simple, it quickly became a problem for us as we took more and more pictures.

We started with a data set of 100 pictures and over winter break managed to expand to about 500 pictures, initially impressive. Yet after developing the neural network, we found our accuracy was unacceptable, about 60%. Up until this point, all data processing (turning of images into coordinates) was done semi-manually and all data was stored on a local hard drive. We played around with the idea of a central website for the group (and maybe some volunteers) to be able to upload their hands, however, we found a much better solution: Goolge Colab and Google Drive.

We created a series of Google Colab scripts in order to streamline data collection and processing:

-

Database structure: This is a data structure created in order to be able to interact with the same Google Drive folder without having to all share the same account. It allows for downloading, uploading, and listing of files based on character.

-

Data collection script (MediaPipe or Openpose): The script records the webcam and take (n) pictures with a delay of (m) milliseconds. We stuck to taking 30 pictures with 300 millisecond delay. This allows us to create a lot of data quickly. After taking the pictures, it uploads them to a Google Drive database of raw images, each file with a unique name.

-

Json creation script (MediaPipe / Openpose): This script will get a list of all raw images and all raw json files. Then the script will process all raw images that have not been found in the raw json folder. It can do this because one image will create one json file of the same name and upload it to the raw json folder.

-

Json formation script (Openpose): This script will download the formed json file for each character (Formed json is the collection of many json files into one json list or object). If the length of the list of the formed json file is equal to the number of raw json files associated with that character, we know that there have been no additional json files added. Otherwise, we will delete the formed_json file (as we cannot discriminately modify the formed json file) and reform it with the data from the raw json folder for that associated character. When all characters are formed, they will combine to create a complete data.json and be uploaded to a unique database that only holds the formed file.

Through the use of these scripts we managed to accumulate more than eight thousand different pictures for sign language characters.

Before the neural network we decided to work on a algorithmic solution in order to get a better idea of the challenges we would face with the network. We developed two different methods:

-

Z-score method: For each frame, take all x coordinates and convert them into z scores and then take all y coordinates and convert them into z scores.

-

Angle method: For each frame, take the angle between each (x, y) coordinate and the next. This will allow the hand to be at any angle (rather than only just head-on).

Both these methods used minimize error min(modeled_coordinate_i - actual_coordinate) in order to predict which sign was being displayed. Of course, the algorithmic approach was unsuccessful. The task is too complicated for a simple algorithm to solve. However, the two methods we came up with heavily influenced on work on the neural network.

Signs such as M and I were mistaken for each other often under the algorithimc approach due to their similiar characteristics.

Working on the neural network, we didn't find much success with simply feeding in the data to the network. Our accuracy was hovering in the 60% range. We assumed that the neural network would figure out how to best interpret the data internally, but we soon got the idea of preprocessing the data in some way. The angle and z-score methods we used in the algorithmic approach made their way back. We hoped that both methods would reduce variability between samples (though they were already normalized) but didn't know which would be more effective. We saw a great boost in our accuracy when we used both methods:

-

Z-score method: ~95% accuracy

-

Angle method: ~75% accuracy

Since the Z-score method was significantly more accurate, we decided to go with that over the angle method.

There also came the problem of network architecture. Research told us that the best layers for the job would be Relu and we tinkered with the number of layers and density, adding some dropoffs and seeing what was optimal. Eventually, we decided to see if we could algorithimically find the most effective architecture and created a script on Google Colab to do so. After many hours of computing time, we procedurally generated 270 different neural networks with different combinations of layer counts,layer types, layer densities and found the most optimal neural network to be cone shaped. Specifically:

Relu(x900) -> Dropout(.15) -> Relu(x400) -> Dropout(.25) -> Tanh(x200) -> Dropout(.4) -> Softmax(x24)

Note that other than rounding the numbers to be more human friendly, the architecture of this neural network was found to be the most optimal by a computer. Even without human biases, the architecture that was developed has a clear pattern to it. Density decreases throughout the layers while dropout increases.

Static characters are an easy start, but it's the dynamic characters which make up most of ASL's vocabulary. When it came to adding the two dynamic signs, we had a series of problems we ran into.

- How long does a sign take? Is there deviation?

- How to deal with FPS variance?

- What instructions to give to data collectors?

- When to use Dynamic neural network and when to use Static?

We found that a sign takes about 1 second, with a large deviation. Unfortuantely, by the time we found out that fact, we had already collected a significant dataset with 3 second data, which may have caused the problems we later ran into.

LSTMs require a static number of inputs. Let's say our LSTM accepts the last 60 frames. If the FPS of the device is 10, the LSTM will process the last 6 seconds of video data - while if the FPS were 30, the LSTM would process the last 2 seconds of video data. It's straightforward to control the last (x) seconds of frames, but it's less so to control the number of frames in the last (x) seconds. At first, we thought about making an LSTM for many different FPS targets and feeding the data into the closest one depending on the current FPS. However, the solution was inelegant. Instead, we created an algorithim called "Video Regulation" which takes in a list of coordinates collected at any FPS and approxmiates an output a list of coordinates at our target FPS (20). You can read more about our regulation script from its developer: Kenny Yip.

We decided to keep it simple and leave it to the data collectors' interpretation. Therefore, we'd have a more diverse dataset. Although, we have come to somewhat regret this decision. Almost all videos started out "clean" and ended with the end of the sign. When we say clean, we mean that there was a lack of random motion surrounding the start and the end of the sign, as there is with real world data. Therefore, the LSTM was not trained to ignore junk data which would be present at the start and end of the sign. We also did not ask for a "none category" of random movements. To the LSTM, all movements were either J or Z . Adding a none category may have discouraged the high probabilities for J/Z given to random hand movements.

Now that we had two neural networks (one for static signs and one for dynamic signs), we had to decide which result to trust and when. At first, we thought that we could feed data into the LSTM first, and if it wasn't too sure about a sign, then it fell to the static neural network to guess the character. However, the LSTM was always sure about what sign it was looking at, even if it clearly wasn't a J/Z so that approach could not be pursued. We decided then that a velocity based system would work well. After about a week of use, we also found this system to have drawbacks. When the hand was close to the camera, velocity was always high. When the hand was further away, it was hard to get SigNN to detect any velocity. Finally, we decided to use a percent change in position system, which is similar to velocity. A percent change in position would scale equally as well with hand movements near and far from the camera. We found this system to be very accurate at detecting when a hand motion is using movement versus movement from just switching between static signs. However, there is the issue that if an experienced signer jumps between characters too fast, that the LSTM would kick in, thinking J/Z was being attempted. The solution to this could be a modified version of our proposed "LSTM first" system. If the LSTM is triggered and probability of any sign is low, the task of predicting gets handed to the static neural network, even if percent change in position is high. However, that would require a more accurate LSTM.

With all the video data we collected, about 800 3 second long videos, we ended up at a theoretical accuracy of 99.5%. Yet, in practice the accuracy turned out to be no better than a coin flip. Even worse, the neural network was very sure that the random data it was seeing was a J or Z, often switching between J and Z from one second to another. One system in place to mitigate the problem is our LSTM analysis system. Rather than simply trusting the LSTM, we feed its output into a data structure that remembers the last (x) seconds of result history. If J was predicted more in the last (x) seconds, then we display J, otherwise Z. There is also an uncertainity threshold baked into the LSTM analysis system. With the new system in place, we had better accuracy than a coin flip, but nowhere near the 99.5% accuray we should have had. In the end, we belive that the lower accuracy in practice is the result of training data which does not map well to the real data which is fed in. While the training data was clean - there is no clean transition in reality. I belive if we had data of many various lengths, rather than 3 seconds long, we could have had a much more accurate LSTM in practice.

Here we can see a small modification to the “hand_tracking_desktop.pbtxt” file found in “/mediapipe/graphs/hand_tracking”. We have the SigNNOneHand subgraph which takes in LANDMARKS and outputs RENDER_DATA. Landmarks are sourced from the HandLandmark subgraph and are a normalized list of 21 (x, y, z) coordinates which represent 21 points on a hand.

This is the SigNNOneHand subgraph, which was a single box in the first picture. We can still see the same LANDMARKS input and RENDER_DATA output, but now we can see all the steps that go between the two.

The first step is the OneHandGate. If too many recent frames did not have a detected hand, it will output SIGNAL, otherwise, it will pass on the LANDMARKS to FPSOneHand and FPSGate. SIGNAL goes into StringToRenderData where it will output “Display 1 hand” to the screen.

What ties the SigNNOneHand subgraph together is the SigNNEndGate calculator. Unlike all other calculators used in SigNN, this calculator has an “ImmediateInputStreamHandler”. Therefore, it will execute when a single input is fulfilled rather than waiting for all inputs. Notice that every gate calculator in the SigNNOneHand subgraph either points at another calculator or has a signal outputting to SigNNEndGate. If a gate outputs a Signal, it will not continue to pass data to the graphs down the line. This is effectively an “if else” command block in graph format, which allows calculators to not be run if they don’t need to be.

FPSGate will display “FPS too low” if the recent average FPS is below 3. At below 3 fps we can no longer accurately interpret which ASL character the user is displaying as motion is required to predict J and Z. Fortunately, the app often runs at much higher FPS values.

Next we find PointVelocityOneHand and LandmarkHistory. PointVelocityOneHand will find the percent change in position of each hand coordinate from frame to frame. It also requires a DOUBLE from the FPSGate, which is the fps. This is required because the formula for velocity is ((new position) - (old position)) / (time_passed). Time passed can be found given the FPS. Velocity is required to know if the sign the user is displaying is a static or dynamic one. Letters [A-Y, excluding J] are static signs - the hand stays still. Letters [J, Z] are dynamic signs - the hand moves to sign them. We will get to the LandmarkHistory calculator later.

Given that there are static and dynamic signs, it is up to the StaticDynamicGate to either push forward the LANDMARK_HISTORY signal (activating the Dynamic neural network) or to push forward the LANDMARKS signal (activating the Static neural network). StaticDynamicGate only takes into consideration the average change in velocity over the last (x) seconds and if the last (y) frames were pushed towards LANDMARK_HISTORY. If the hand’s average movement falls below the dynamic threshold but there is sufficient history of movement, it will continue to push forward the Dynamic neural network so that the [J, Z] result does not disappear the second the user’s hand stops moving.

The LandmarkHistory calculator keeps the last (x) seconds of data in memory. Since the dynamic neural network makes use of an LSTM, we must feed it the history of movement every time we would like to get a prediction output.

This is what the inside of the SigNNDynamic subgraph looks like. First, the data is regulated to a certain number of frames. Since we know that the data is from the last (x) seconds, and we have the last (y) number of frames through LANDMARKS_HISTORY, we can modify the data to be (z) FPS through our regulation algorithm. The FPS must be static because our LSTM was trained on 20FPS data.

After being regulated, the data runs through the z-score calculator. It finds the mean and standard deviation of the x and y coordinates over the entire LANDMARK_HISTORY and changes them to z_scores accordingly. The z coordinate was forgotten when the LANDMARK_HISTORY was recorded because we found that it significantly lowered our accuracy.

The LandMarkHistoryToTensor, TfLiteConverter, and TfLiteInference calculators are required to run our LSTM.

DynamicTfLiteTensorsToCharacter has the difficult job of interpreting the LSTM’s data. If we simply output what the LSTM believed was the correct answer in the moment, it would constantly flip flop between J and Z. Therefore, the job of this calculator is to keep in memory how many times the LSTM predicted J and Z within the past (x) seconds. If either character passes a threshold of being predicted (y)% of the last (z) frames, it is outputted. If no character passes the threshold, “Unknown” is outputted.

This is the SigNNStatic subgraph. It is very similar to the SigNNDynamic subgraph, with a few key changes. Firstly, it does the Zscore of the hand rather than of a hand history, so it must use a different calculator. It also makes use of a TimeAverage calculator, where the last (x) seconds of hands are averaged rather than feeding raw data. This helps to overcome glitches that can happen with Mediapipe’s hand tracking neural network under adverse conditions.

The TfLiteTensorsToCharacter calculator has a similar job to its dynamic counterpart, but a much simpler one. It will receive the prediction of the fully connected neural network that we trained on [A-Y, minus J] and add a last character bias of (x)% to it. Simply, if on the last frame it predicted the letter B, it will give the neural network a (x)% nudge towards B for this frame as well. This prevents constant flip-flopping between signs which may look similar. If the neural network is not at least (y)% confident about any character being the correct sign (including taking the bias into account), it will output “Unknown”.

This concludes the look into the SigNNOneHand subgraph, which is displayed again below for review.

This is the SigNNStatic subgraph. It is very similar to the SigNNDynamic subgraph, with a few key changes. Firstly, it does the Zscore of the hand rather than of a hand history, so it must use a different calculator. It also makes use of a TimeAverage calculator, where the last (x) seconds of hands are averaged rather than feeding raw data. This helps to overcome glitches that can happen with Mediapipe’s hand tracking neural network under adverse conditions.

The TfLiteTensorsToCharacter calculator has a similar job to its dynamic counterpart, but a much simpler one. It will receive the prediction of the fully connected neural network that we trained on [A-Y, minus J] and add a last character bias of (x)% to it. Simply, if on the last frame it predicted the letter B, it will give the neural network a (x)% nudge towards B for this frame as well. This prevents constant flip-flopping between signs which may look similar. If the neural network is not at least (y)% confident about any character being the correct sign (including taking the bias into account), it will output “Unknown”.

This concludes the look into the SigNNOneHand subgraph.

-

Real-time translation of sign language is a computationally difficult task that may not be possible on most consumer-grade hardware. However, new libraries such as MediaPipe are starting to make mobile real-time sign language translation possible.

-

One of the largest obstacles to the creating of a neural network for the translation of sign language is the lack of publicly available sign language data. Possible solution could be to crowdsource data collection.

-

The collection, management, and processing of training data is a task which cannot feasibly be done manually, and should be streamlined.

-

Sign language translation cannot be accurately done in an algorithmic approach as many signs look very similar when it (x, y) coordinate form. It is necessary to use a neural network.

-

Coordinate data from pictures is not optimal input to a translation neural network. Accuracy rates increase (81% -> 95% in our case) when each frame has z-scores individually calculated for each set of x and y coordinates.

-

We were able to complete real-time translation of characters A-Y (excluding J) with 95% accuracy. J, Z with 99% accuracy.

-

ASL Characters J and Z along with almost all ASL words are "time-series" signs that will require the use of an LSTM and complex data management infrastructure.

We hope to see the field of ASL translation grow in the future. From here, multi-hand support should be added to the translation process (which is already supported by MediaPipe). It will be important to tell if a hand is a left hand or a right hand (a feature not supported by MediaPipe as of October 2020). Using MediaPipe's Pose tracking in conjunction with more detailed hand tracking may be the way forward for the complex, multi-hand signs that words achive. Finally, there is phase III which would transform the program from a translator, to an interpreter.